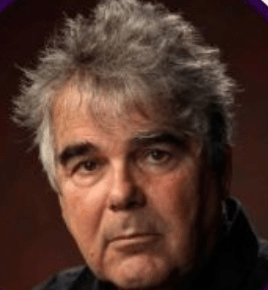

In October, FFIMI and the Bridgewater State Hospital Family and Friends were honored to sponsor Frans Douw, a global humanitarian with more than 50 years of experience in closed institutions. He has worked with juveniles, forensic psychiatry, and has been a warden in several houses of detention and prisons for men and women in the Dutch Prison System. He is currently involved with international knowledge exchange projects addressing prison mental health and forensic psychiatry within the scope of human rights with Russia, almost all former Soviet countries, Great Britain, the Caribbean and the USA.

Frans brought his decades of experience and proven success to Massachusetts, forming a strong connection with everyone he met. He came to listen to the people working inside our correctional and forensic systems, and to the people living within them. He followed up with a report to be shared with Commissioner Shawn Jenkins of the Massachusetts Department of Corrections offering his observations and recommendations.

About the Visit

With the cooperation of the Massachusetts Department of Corrections, three days of tours and meetings were planned at Old Colony Correctional Center (OCCC) and Bridgewater State Hospital (BSH). Importantly, Frans was granted permission to visit with several inmates and forensic patients at BSH & OCCC.

For those who may not know:

- BSH is a Massachusetts, secure forensic facility for men under the jurisdiction of the Department of Correction (DOC). For years the Disability Law Center, FFIMI, and countless families have advocated that BSH belongs under the Department of Mental Health (DMH) instead of the DOC.

- Nearby, OCCC is a medium-security correctional facility with a mental health focus.

What Frans Saw — His Impressions

In his report, Frans expressed gratitude to everyone he met and emphasized the professionalism and dedication of staff members he encountered. He noted that he experienced nothing but genuine hospitality and trust throughout his time.

But he also saw what we all know too well: systems that perpetuate suffering. Despite the good intentions of many staff, the structure and environment of these institutions remain rooted in punishment rather than treatment. Frans noted: “First and foremost, the difference between a prison directed to punishment and control and a facility that supports recovery and respects human dignity is the way we look at the people who are incarcerated.”

It is accepted and part of the culture in prisons all over the world to suppress, limit and punish the incarcerated population. Not treating them as people like you and me, like our family who unfortunately got into a situation which could happen to everybody, including ourselves. And that those people, like us, deserve every support and respect possible to be able to recover from trauma and illness and get a meaningful life back, inside and outside the facility. And that we must treat them exactly as we, as “normal” people, want to be treated.

A Simple Gesture — A Cup of Coffee

At OCCC, nine incarcerated individuals were granted private meetings with Frans, and each walked away deeply affected. He offered genuine respect and showed a real desire to understand their lived experiences. In an environment where humanity is often scarce, the simplest acts can carry profound weight.

One moment in particular captured this idea perfectly. At the start of one of his meetings, a captain on duty walked in and offered Frans a cup of coffee, without acknowledging the incarcerated person sitting beside him. Frans smiled and replied, “Yes, and for my friend here as well.”

It was a small gesture, but in this setting, it landed with tremendous significance. In that moment, Frans made clear that the person across from him mattered, as a human being worthy of equal regard.

A Positive Exercise at BSH

In the excerpt below, Frans shares an example of a person-focused exercise.

I had a meeting with ten incarcerated people and two staff members in the library at BSH. I explained that I know that the people that are present are seen as psychiatric patients and staff members. But that each one of them is so much more than that. I suggested that we make a round in which everybody tells something about other skills, competences, hobbies and experiences that they have. The harvest was rich: people know how to grow food, worked as a farmer, know how to fish, how to cook, drove a lorry with fish, know everything about the fish-industry, worked in a sushi bar, can work with computers and teach and coach other people. At the end of the meeting, we concluded that it would be a great idea to start a fish-restaurant in the centre of BSH, train the ones who want to learn hospitality and cooking and serve an excellent meal for staff and incarcerated people.

What an Effective Living Climate Includes

Drawing on international research, Frans outlined seven essential aspects of an effective living climate, the foundation of a humane correctional environment. His focus was on the following areas:

- Relationship between staff and patients/inmates

- Autonomy – being able to make as many choices as possible within the context you are in

- Connection with families and the outside world

- Meaningful activities

- Proper Care and Treatment

- Physical Environment

- Security Measures that limit possibilities

Frans explained that changes can be made in these categories and they need not be expensive. He described the following powerful ways Massachusetts could move closer to this model such as:

- Decrease unnecessary restrictions that don’t enhance safety – Small procedural changes such as less time locked in, easier access to programming, and more flexible movements.

- Create more opportunities for “staff/inmate/patient” interaction – Simple things like shared meals, group conversations, collaborative activities, and sitting together over a cup of coffee serve to restore a sense of dignity and reduce the “us vs. them” divide.

- Expand peer mentoring and peer-led programs – Support systems led by trained incarcerated mentors help build responsibility, reduce isolation, and empower people to support one another’s growth.

- Include people who are incarcerated in solution-building – Invite them to participate in discussions, feedback loops, and planning; this increases buy-in and avoids top-down reforms that don’t match lived experience.

- Increase opportunities for family and community connection – Family ties are the strongest predictors of successful reentry; expanding visiting access and communication supports rehabilitation at no real financial cost.

- Normalize the environment wherever possible – Small environmental improvements like access to natural light, open spaces, color, and art go a long way in helping mood and behavior.

Reflections from Voices Behind the Wall

After the one-on-one meetings at OCCC, the inmates who met with Frans gathered in a roundtable conversation to process what they had experienced. The sense of hope in the room was unmistakable and it rippled outward to others who hadn’t been able to meet with Frans directly but still felt encouraged just knowing he had been there. Below are excerpts from the letters they later wrote to Frans, attempting to express what that hope meant to them.

Knowing there is someone out there willing to listen — not just listen, but hear you and want the best for your future…made me realize there is some hope. The light at the end of the tunnel might not be a train. ~Jessie Brothers

Jessie, who entered the system at age 12, spoke about a lifetime of feeling discarded and how one real conversation about healing gave him something unfamiliar: hope.

I’ve been in 25-plus years and never have I sat down and talked to administration about anything… I’ll never forget how present you made me feel. ~Corey Stokes

Corey described the transformation from a scared 17-year-old with a life sentence into a man committed to healing childhood trauma. What struck him most wasn’t a program, it was being treated with respect (and a cup of coffee!).

I hope we can stay connected… with training and updated technology, so that when we return to society we are able to know how technology works, improve better education skill, trades, and better serve this evolving community. ~Isaac Wallace

Isaac advocates for tools that would allow people to reenter society with skills, confidence, and dignity.

Life sentences here in America are given out like candy… with no chances for rehabilitation. Frans is… intelligent, and I hope the DOC takes prison reform advice from him. ~Ella Bynum-Harris

Ella spoke of the stark contrast between Europe’s rehabilitative model and America’s punitive system.

We are all still feeling encouraged and inspired… It was such an immense pleasure to meet you. ~Ben Walsh

Ben is a dog handler at OCCC as part of the America’s VetDogs Prison Puppy Program. Frans shared with Ben about the Dutch Cell Dogs Program. He and Frans connected deeply and plan to stay in touch and exchange ideas and experiences and continued ways to bring positive change.

[Mr. Douw’s visit] provided one of the most important things that is hard to find within these fences: HOPE. Hearing someone from outside advocating that we be treated in a humane and dignified manner provides a light in the dark tunnel which we often feel trapped in. ~Robert W. Anderson

Robert has been incarcerated for thirty-six years and lives with severe mental illness, a combination that, as he wrote, can make daily life inside feel like “a dark tunnel.” Frans’ visit offered him something he rarely encounters: genuine hope.

A Few Recommendations – “Low Hanging Fruit”

We must go from “system- based” towards “people based”… and that being respectful is the most effective way to treat people.

Frans states in his report “The implementation of the development needed asks for a very different approach of all involved and it is essential that incarcerated people and staff are trusted to be the owners of this change.

He advises the following “low hanging fruit”:

- Install a taskforce of a mixed group of incarcerated people, staff, management and formerly incarcerated people who will develop a “plan for change”. Start with the training of this group by experienced trainers from the Department of Mental Health (if possible, from Massachusetts or from elsewhere in the US). Be sure to involve peer educators as co-trainers.

- Install an independent oversight committee with, amongst others, a loved one, a staff member, experienced experts and mental health experts. This group can handle complaints and monitor the changing-process.

- Be sure the organizational change is scientifically followed and researched, for example by a professor and students of Harvard Business School.

Frans’s visit left many with a renewed sense of possibility. Especially meaningful was hearing people who rarely feel seen light up with hope simply because someone took the time to hear them.

Frans’s visit reminded us that change is not only necessary but possible. Massachusetts is capable of transformational change. We can create environments that promote dignity, safety, and healing. We can shift from a punitive system of management to a culture of dignity and restoration.

Gratitude

This visit was made possible through the support and openness of Commissioner Shawn Jenkins, Deputy Commissioner Mitzi Peterson, and other DOC leaders, whose willingness to engage in dialogue opened the door for these conversations. FFIMI is deeply grateful for their collaboration and for the gracious hospitality and trust they offered to Frans.

FFIMI would especially like to express our heartfelt appreciation to Frans Douw – for his willingness to listen deeply, to learn with humility, to lead with courage, and to show a kind of love that reminds people of their own worth.

His presence here made a real difference, and we are profoundly grateful.

More about Frans Douw

- Frans Douw began his career in 1975 working with juveniles and later served in the Dutch prison system’s forensic psychiatric assessment clinic (1978–1988). From 1988 to 2015, he was warden and director of multiple correctional and forensic psychiatric institutions, including five penitentiary facilities across three cities housing both short-term and long-term (including life-sentence) populations.

- Since 1999, he has been deeply involved in international knowledge-exchange on prison mental health, forensic psychiatry, and human rights, collaborating with partners in Russia, former Soviet states, Great Britain, the Caribbean, and the United States. His work has been carried out independently as well as in partnership with the Dutch Ministry of Justice, the Global Initiative on Psychiatry, Mainline, the ICRC, the WHO/UN, and the Council of Europe.

- Frans is also an author, founder of the Recovery and Return Foundation, podcast host, lecturer, and a frequent contributor to Dutch television, radio, and print media.

- Read more about Frans Douw and his work here.